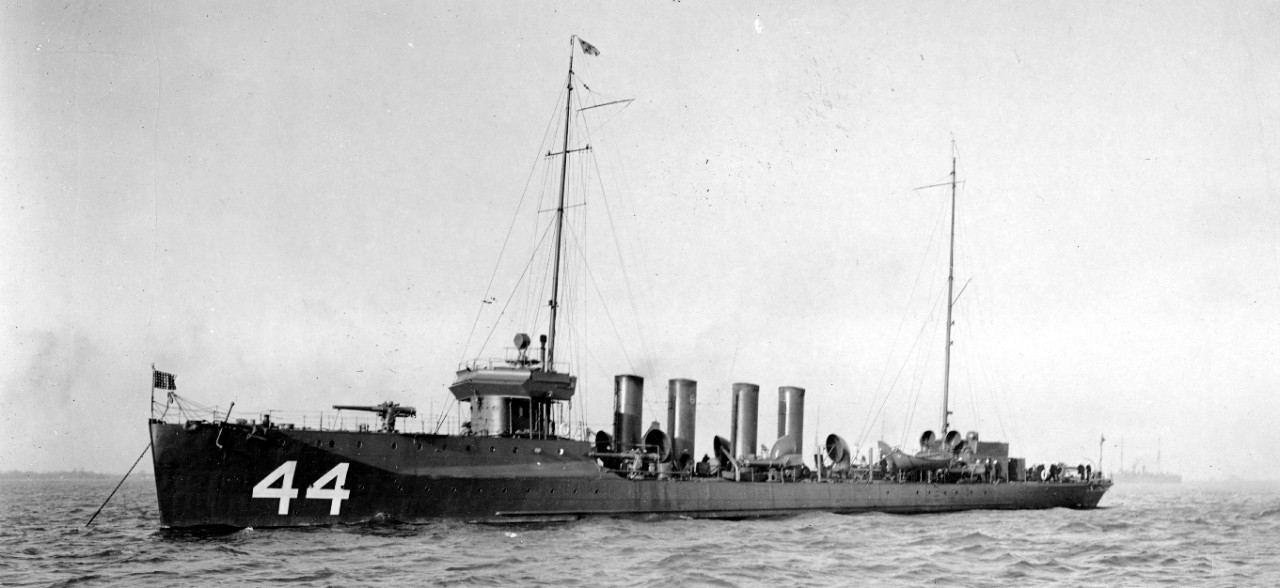

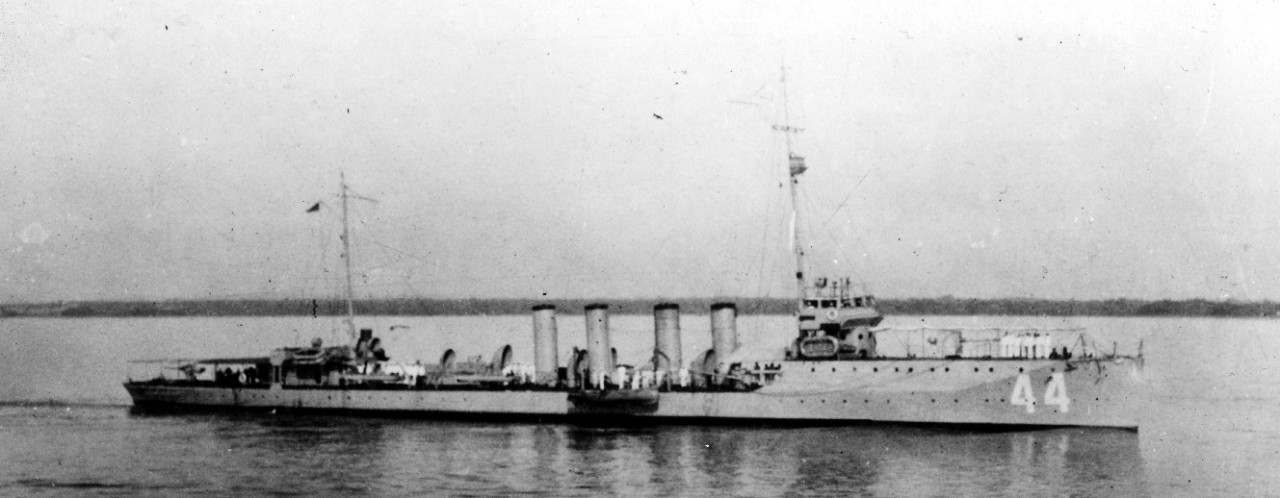

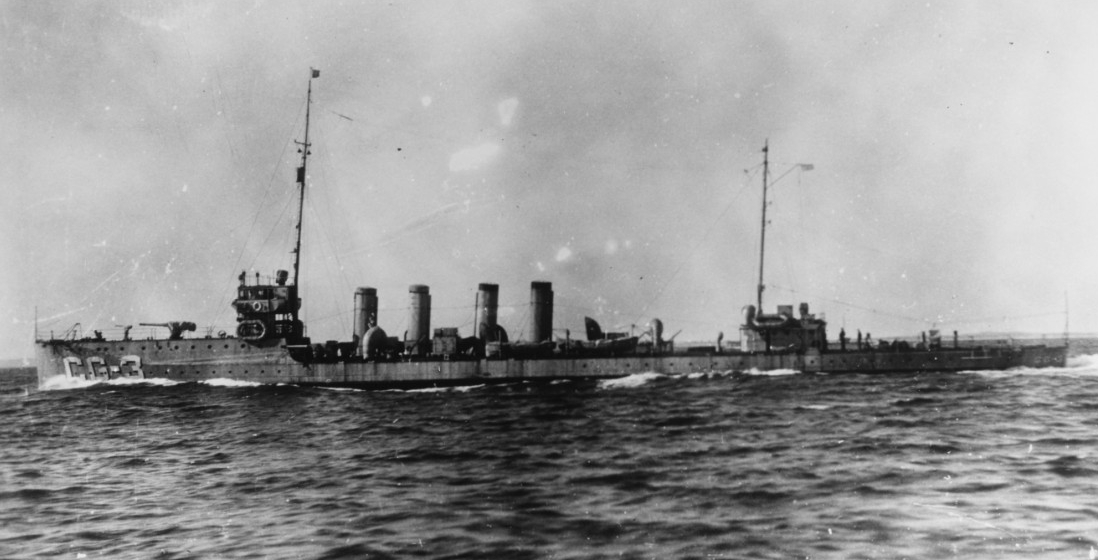

Hull Number: DD-44

Launch Date: 08/06/2013

Commissioned Date: 09/19/2013

Decommissioned Date: 06/23/2022

Other Designations: USCG(CG-3)

Class: CASSIN

CASSIN Class

Namesake: ANDREW BOYD CUMMINGS

ANDREW BOYD CUMMINGS

Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, April 2017

Andrew Boyd Cummings — born in Philadelphia, Pa. on 22 June 1830 — was appointed midshipman from the state of Pennsylvania in 1847. After examination, the Secretary of the Navy appointed him acting Midshipman on 7 April 1847. On 3 August of the same year, with the Mexican-American War raging, he was detached from the Naval Academy and ordered to Norfolk to embark in the frigate Brandywine and proceed to Brazil where he would report to the ship-of-the-line Ohio. He then served off the coast of Brazil until Ohio rounded Cape Horn to blockade Mexican ports in the Pacific. By the time Ohio reached Mazatlán, however, the war was over, but despite her tardy arrival she rendered important services to locals in Baja California who cooperated with Americans during hostilities, evacuating them when the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo left the southern territory to Mexico.

While the big warship missed the war, conflict of an altogether different kind broke out on board Ohio and within the Pacific squadron. As the ships patrolled offshore in the summer of 1848, gold fever seized California and the prospect of riches beckoned sailors earning far less pay than they could attain in the gold fields. Desertion and the threat of mutiny became a serious problem, forcing commanding officers to confine their crews on board and keep them at sea. The draconian system pitted the crews against officers and junior officers against their superiors. In addition, confinement on board and high local prices for fresh food led to scurvy among the crew. Amidst those troubled times, Cummings received his midshipman’s warrant in December 1849, and his momentous first voyage ended in April 1850 when Ohio returned east.

In the summer of 1850 Cummings served in the sloop-of-war St. Mary’s for a month before transferring to sloop Saratoga on 20 August. He came back to the Pacific and served with the East India Squadron, returning in June 1852 in the sloop-of-war Marion with orders to report to the Naval Academy after five years’ absence. Ordered to the side-wheel steamer Fulton on 15 June 1853 and informed of his promotion to passed midshipman, he received further advancement — to lieutenant — in September 1855, and served in the Home Squadron until November 1855. He reported to the receiving ship at Philadelphia and remained there until April 1857 when he began service in the sloop-of-war Dale, which operated against the slave trade off of the coast of Africa. He returned to the receiving ship at Philadelphia and waited there until the early autumn of 1860 when he reported for duty on board the new wooden steam-sloop Richmond, that set course for the Mediterranean on 13 October with the contentious presidential election of 1860 less than one month away and the nation careening toward fratricidal conflict.

Soon after the outbreak of the Civil War, Richmond steamed back across the Atlantic, arriving in New York in July 1861. There, she refitted, then steamed to the Caribbean in search of the cruiser Sumter (Capt. Raphael Semmes, CSN, commanding), but the Confederate warship escaped and Richmond joined the Federal squadron blockading the Mississippi, patrolling off the mouth of the river near New Orleans as the flagship of a small squadron. The Confederate “Mosquito Fleet” guarding New Orleans confronted the Federal squadron at “The Battle of the Head of the Passes.”

The cigar-shaped rebel ironclad Manassas rammed Richmond and the mosquito fleet loosed three fire ships to drift downriver at the U.S. vessels. The Federal ships frantically sailed and steamed toward open waters as Richmond covered the retreat. In the subsequent panic, Richmond and the sloop Vincennes ran aground and suffered fire from sea and shore, fortunately escaping without any fatalities. Naval officers viewed the battle as a disgrace and the commander of the blockade relieved Richmond’s captain two weeks later. The ship continued to patrol the mouth of the river until November when she underwent temporary repairs.

Under Captain Francis B. Ellison, her new commanding officer, Richmond engaged Forts Pickens and McRee at Pensacola on 22 November 1861, suffering damage and casualties from Confederate fire on the second day but heavily damaging the fort during the bombardment. Richmond returned to New York for repairs, then set course for the Gulf of Mexico in February 1862 and joined Flag Officer David G. Farragut’s West Gulf Blockading Squadron off the coast of New Orleans in early March. The squadron soon engaged Forts Jackson and St. Philip protecting the approaches to the city. As Cmdr. David Dixon Porter shelled the forts beginning on 18 April, Richmond and the remainder of the squadron dodged Confederate fire ships, and the battle reached its climax in the early morning of 24 April when Farragut led the squadron past the forts. Hit 17 times above the waterline, Richmond suffered a glancing blow from a ram but effective chain armor staved off heavy damage and casualties. Despite the precautions, however, two members of the crew died and several suffered wounds. The attack bypassed the forts and defeated and badly bloodied the Rebel squadron, and the maneuver left New Orleans open and the city fell to the Federal ships on 28 April. Richmond’s new commanding officer, Cmdr. James Alden, lauded his crew, and particularly singled out Lt. Cummings, his executive officer, giving him credit for the success of the ship in the recent battle. “By his [Cummings’] cool and intrepid conduct the batteries were made to do their whole duty,” Alden wrote, “not a gun was pointed or a shot sent without his mark.”

After helping consolidate the Navy’s hold on territory in Louisiana and Mississippi along the Mississippi, Richmond took position below Vicksburg in early July 1862. Farragut’s squadron, with Richmond in company, successfully passed the city, exchanging heavy fire on 28 June 1862. She was present when Farragut’s fleet joined with Commodore Charles H. Davis’ Western Flotilla above Vicksburg on 1 July. Richmond again suffered casualties and damage similar to that she had received during the New Orleans campaign. Cmdr. Alden again lauded Cummings as the individual most worthy of praise, claiming that the “careful training and consequent steadiness of the crew,” was due to Cummings’ leadership and concluded “I trust that a grateful country will soon reward him in some way for his untiring zeal and devotion to his profession and her cause.”

On 15 July 1862, the Confederate casemate ram Arkansas emerged from her lair in the Yazoo River and ran past the Union Fleet above Vicksburg. Although hotly pursued by Richmond and other ships, the ram escaped to shelter under the Confederate batteries at Vicksburg. Cummings received to lieutenant commander on 16 July when an act of Congress created the position. Farragut’s fleet again raced past Vicksburg and Richmond continued to escort supply steamers and provide shore bombardment support. The squadron returned to New Orleans on 28 July being unable to threaten Vicksburg without corresponding effort from ground forces.

While Richmond lay downriver on the lower Mississippi, Confederate forces constructed strong and well-armed fortifications at Port Hudson, Louisiana, that guarded a sharp bend in the river, treacherous to pass under fire. On 14 March 1863, the Union forces planned a joint operation consisting of ground forces under General Nathanial Banks and riverine forces under Rear Adm. Farragut, utilizing ground forces to distract defenders and allow the squadron to pass the fortifications. After passing the guns, naval forces would control the river north of the works, denying river-borne supplies and munitions as well as establishing communications with the Federal squadron remaining at Vicksburg. Farragut picked seven vessels for the operation, including Richmond.

By 5:00 p.m. on 14 March 1863, General Banks sent word that his troops were approaching the town, to which Rear Adm. Farragut replied that he would pass the batteries before midnight. Richmond, lashed to the gunboat Genesee, formed up as the second pair of vessels in the column behind Farragut’s flagship, the sloop Hartford. Shortly past 9:00 p.m., the squadron worked up steam and plowed up river through the dark. Three miles of the river bank studded with rebel batteries greeted the squadron, and at 11:10 p.m., the shore seem to explode with cannon fire.

On Richmond’s bridge, Cummings calmly directed fire through his speaking trumpet: “You will fire the whole starboard battery, one gun at a time, from bow gun aft. Don’t fire too fast, aim carefully at the flashes of the enemy guns. Fire!” The gun crews fired shrapnel, shell, grape, and canister, silencing batteries and small arms fire along the way. From his vantage point on board Hartford, the admiral noticed Lt. Cmdr. Cummings’ handiwork. “When we rounded the bend I saw the Richmond,” Farragut later wrote in approbation, “and the effect of each of her broadsides upon the batteries.” As the sloop ran the gauntlet, however, the combination of the darkness and smoke, the latter exacerbated by high humidity, limited vision and slowed her progress. As Richmond approached the turn, Confederate guns found their mark and raking fire began to take a toll on the ship and her crew. Throughout those harrowing moments, Cummings remained on the bridge, relaying orders and encouraging the gunners.

Suddenly, Cummings crumpled to the deck, struck by artillery fire that carried off his left leg below the knee. Cmdr. Alden later recalled that his executive officer bravely beseeched his men: “Quick, boys; pick me up; put a tourniquet on my leg; send my letters to my wife; tell them I fell doing my duty.” Carried below, Cummings gamely insisted that surgeons treat other wounded first. Richmond’s misfortunes, however, continued. Soon after enemy fire felled her hardy executive officer, a torpedo [mine] exploded close astern causing minor damage. Much more serious damage resulted when a six-inch rifle solid shot hulled Richmond and destroyed several pieces of machinery, letting off steam and putting the fires out, effectively stopping the sloop dead in the water.

Unable to maneuver and taking heavy fire from the Rebel batteries, Cmdr. Alden ordered the vessel’s head turned downstream to drift out of danger. When surgeons informed Cummings of the development, he exclaimed “I would rather lose the other leg than go back; can nothing be done? There is a south wind; where are the sails?” Genesee towed the sloop to safety below the guns of Port Hudson.

Daybreak revealed grisly scenes on Richmond’s deck and throughout the squadron. Three of Richmond’s crew died in the initial fighting and twelve lay wounded. Of Farragut’s squadron, only his flagship Hartford and the gunboat lashed to her side passed Port Hudson successfully. Among the remaining five vessels, four suffered severe damage and the crew of the paddle frigate Mississippi abandoned ship, setting her afire to deprive the Rebels of her use. Richmond picked up the majority of Mississippi’s crew and they were milling around on the splintered and blood-stained deck when Cummings was borne ashore, rushed to New Orleans for treatment. Although he departed Richmond appearing “quite well,” Cummings succumbed to his wounds and died in the city on 18 March 1863 at the age of 32.

“It has pleased God to take from among us our gallant friend in the fullness of his energies and usefulness,” Cmdr. Alden told his grieving crew as he eulogized the fallen executive officer, “You all well know the importance of his services in this ship; his conscientious devotion to duty; his justice and even temper in maintaining discipline; his ability in preparing for emergencies, and his coolness in meeting them. All these qualities he brought to his country in the hour of need, and he has sealed his devotion with his life.”

Cummings was buried on 7 September 1864 in his family plot at Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia.

Disposition:

Loaned to the Coast Guard 6/7/1924 - 5/23/1932. Stricken 7/5/1934. Scrapped 1934.