Hull Number: DDG-72

Launch Date: 06/29/1996

Commissioned Date: 02/14/1998

Call Sign: NBTF

Class: ARLEIGH BURKE

ARLEIGH BURKE Class

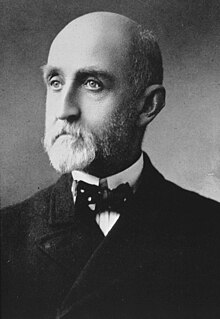

Namesake: ALFRED THAYER MAHAN

ALFRED THAYER MAHAN

Wikipedia (as of 2024)

Alfred Thayer Mahan (/məˈhæn/; September 27, 1840 – December 1, 1914) was a United States naval officer and historian, whom John Keegan called “the most important American strategist of the nineteenth century.”[1] His book The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660–1783 (1890) won immediate recognition, especially in Europe, and with its successor, The Influence of Sea Power Upon the French Revolution and Empire, 1793–1812 (1892), made him world-famous.[2]

Mahan was born on September 27, 1840, at West Point, New York, to Dennis Hart Mahan,[3] a professor at the United States Military Academy and the foremost American expert on fortifications, and Mary Helena Okill Mahan (1815–1893), daughter of John Okill and Mary Jay, daughter of Sir James Jay. Mahan’s middle name honors “the father of West Point”, Sylvanus Thayer. Mahan attended Saint James School, an Episcopal college preparatory academy in western Maryland. He then studied at Columbia for two years, where he was a member of the Philolexian Society debating club.[4] Against the better judgment of his father, Mahan then entered the U.S. Naval Academy, where he graduated second in his class in 1859.[5]

After graduation he was assigned to the frigate Congress from 9 June 1859 until 1861. He then joined the steam-corvette Pocahontas of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron and participated in the Battle of Port Royal in South Carolina early in the American Civil War.[6] Commissioned as a lieutenant in 1861, Mahan served as an officer on USS Worcester and James Adger and as an instructor at the Naval Academy. In 1865, he was promoted to lieutenant commander, and then to commander (1872), and captain (1885). As commander of the USS Wachusett he was stationed at Callao, Peru, protecting U.S. interests during the final stages of the War of the Pacific.[7][8]

While in actual command of a ship, his skills were not exemplary; and a number of vessels under his command were involved in collisions with both moving and stationary objects. He preferred old square-rigged vessels rather than smoky, noisy steamships of his own day; and he tried to avoid active sea duty.[9]

In 1885, he was appointed as a lecturer in naval history and tactics at the Naval War College. Before entering on his duties, College President Rear Admiral Stephen B. Luce pointed Mahan in the direction of writing his future studies on the influence of sea power. During his first year on the faculty, he remained at his home in New York City researching and writing his lectures. Though he was prepared to become a professor in 1886, Luce was given command of the North Atlantic Squadron, and Mahan became President of the Naval War College by default (June 22, 1886 – January 12, 1889, July 22, 1892 – May 10, 1893).[10] There, in 1888, he met and befriended future president Theodore Roosevelt, then a visiting lecturer.[11]

Mahan’s lectures, based on secondary sources and the military theories of Antoine-Henri Jomini, became his sea-power studies: The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783 (1890); The Influence of Sea Power upon the French Revolution and Empire, 1793–1812 (2 vols., 1892); Sea Power in Relation to the War of 1812 (2 vols., 1905), and The Life of Nelson: The Embodiment of the Sea Power of Great Britain (2 vols., 1897). Mahan stressed the importance of the individual in shaping history and extolled the traditional values of loyalty, courage, and service to the state. Mahan sought to resurrect Horatio Nelson as a national hero in Britain and used his biography as a platform for expressing his views on naval strategy and tactics. Mahan was criticized for so strongly condemning Nelson’s love affair with Lady Emma Hamilton, but it remained the standard biography until the appearance of Carola Oman‘s Nelson, 50 years later.[12]

Mahan struck up a friendship with pioneering British naval historian Sir John Knox Laughton, the pair maintaining the relationship through correspondence and visits when Mahan was in London. Mahan was later described as a “disciple” of Laughton, but the two were at pains to distinguish between each other’s line of work. Laughton saw Mahan as a theorist while Mahan called Laughton “the historian”.[13] Mahan worked closely with William McCarty Little, another critical figure in the early history of the Naval War College. A principal developer of wargaming in the United States Navy, Mahan credited Little for assisting him with preparing maps and charts for his lectures and first book.[citation needed]

Origin and limitation of strategic views[edit]

Mahan’s views were shaped by 17th-century conflicts between the Dutch Republic, the Kingdom of England, the Kingdom of France, and Habsburg Spain, and by the naval conflicts between France and Spain during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. British naval superiority eventually defeated France, consistently preventing invasion and an effective blockade. Mahan emphasized that naval operations were chiefly to be won by decisive battles and blockades.[14] In the 19th century, the United States sought greater control over its seaborne commerce in order to protect its economic interests which relied heavily on exports bound mainly for Europe.

According to Peter Paret‘s Makers of Modern Strategy from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age, Mahan’s emphasis on sea power as the most important cause of Britain’s rise to world power neglected diplomacy and land arms. Furthermore, theories of sea power do not explain the rise of land empires, such as Otto von Bismarck‘s German Empire or the Russian Empire.[15]

Mahan believed that national greatness was inextricably associated with the sea, with its commercial use in peace and its control in war; and he used history as a stock of examples to exemplify his theories, arguing that the education of naval officers should be based on a rigorous study of history. Mahan’s framework derived from Jomini, and emphasized strategic locations (such as choke points, canals, and coaling stations), as well as quantifiable levels of fighting power in a fleet. Mahan also believed that in peacetime, states should increase production and shipping capacities and acquire overseas possessions, though he stressed that the number of coal fueling stations and strategic bases should be limited to avoid draining too many resources from the mother country.[16]

The primary mission of a navy was to secure the command of the sea, which would permit the maintenance of sea communications for one’s own ships while denying their use to the enemy and, if necessary, closely supervise neutral trade. Control of the sea could be achieved not by destruction of commerce but only by destroying or neutralizing the enemy fleet. Such a strategy called for the concentration of naval forces composed of capital ships, not too large but numerous, well-manned with crews thoroughly trained, and operating under the principle that the best defense is an aggressive offense.[17]

Mahan contended that with a command of the sea, even if local and temporary, naval operations in support of land forces could be of decisive importance. He also believed that naval supremacy could be exercised by a transnational consortium acting in defense of a multinational system of free trade. His theories, expounded before the submarine became a serious factor in warfare, delayed the introduction of convoys as a defense against the Imperial German Navy‘s U-boat campaign during World War I. By the 1930s, the U.S. Navy had built long-range submarines to raid Japanese shipping; but in World War II, the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces, still tied to Mahan, designed its submarines as ancillaries to the fleet and failed to attack American supply lines in the Pacific. Mahan’s analysis of the Spanish-American War suggested to him that the great distances in the Pacific required the American battle fleet to be designed with long-range striking power.[18]

Mahan believed first, that good political and naval leadership was no less important than geography when it came to the development of sea power. Second, Mahan’s unit of political analysis insofar as sea power was concerned was a transnational consortium, rather than a single nation state. Third, his economic ideal was free trade rather than autarky. Fourth, his recognition of the influence of geography on strategy was tempered by a strong appreciation of the power of contingency to affect outcomes.[19]

In 1890, Mahan prepared a secret contingency plan for war between the British Empire and the United States. Mahan believed that if the Royal Navy blockaded the East Coast of the United States, the US Navy should be concentrated in one of its ports, preferably New York Harbor with its two widely separated exits, and employ torpedo boats to defend the other harbors. This concentration of the U.S. fleet would force the British to tie down such a large proportion of their navy to watch the New York exits that other American ports would be relatively safe. Detached American cruisers should wage “constant offensive action” against the enemy’s exposed positions; and if the British were to weaken their blockade force off New York to attack another American port, the concentrated U.S. fleet could capture British coaling ports in Nova Scotia, thereby seriously weakening British ability to engage in naval operations off the American coast. This contingency plan was a clear example of Mahan’s application of his principles of naval war, with a clear reliance on Jomini’s principle of controlling strategic points.[20]

Timeliness contributed no small part to the widespread acceptance of Mahan’s theories. Although his history was relatively thin, based as it was on secondary sources, his vigorous style, and clear theory won widespread acceptance of navalists and supporters of the New Imperialism in Africa and Asia.

Given the rapid technological changes underway in propulsion (from coal to oil and from reciprocating engines to turbines), ordnance (with better fire directors, and new high explosives), and armor and the emergence of new craft such as destroyers and submarines, Mahan’s emphasis on the capital ship and the command of the sea came at an opportune moment.[17]

|

Alfred Thayer Mahan

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | September 27, 1840 West Point, New York, U.S. |

| Died | December 1, 1914 (aged 74) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Buried |

Quogue Cemetery

Quogue, New York |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1859–1896 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | USS Chicago USS Wasp USS Wachusett |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

| Signature | |

Alfred Thayer Mahan (/məˈhæn/; September 27, 1840 – December 1, 1914) was a United States naval officer and historian, whom John Keegan called “the most important American strategist of the nineteenth century.”[1] His book The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660–1783 (1890) won immediate recognition, especially in Europe, and with its successor, The Influence of Sea Power Upon the French Revolution and Empire, 1793–1812 (1892), made him world-famous.[2]

Early life[edit]

Mahan was born on September 27, 1840, at West Point, New York, to Dennis Hart Mahan,[3] a professor at the United States Military Academy and the foremost American expert on fortifications, and Mary Helena Okill Mahan (1815–1893), daughter of John Okill and Mary Jay, daughter of Sir James Jay. Mahan’s middle name honors “the father of West Point”, Sylvanus Thayer. Mahan attended Saint James School, an Episcopal college preparatory academy in western Maryland. He then studied at Columbia for two years, where he was a member of the Philolexian Society debating club.[4] Against the better judgment of his father, Mahan then entered the U.S. Naval Academy, where he graduated second in his class in 1859.[5]

Early career[edit]

After graduation he was assigned to the frigate Congress from 9 June 1859 until 1861. He then joined the steam-corvette Pocahontas of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron and participated in the Battle of Port Royal in South Carolina early in the American Civil War.[6] Commissioned as a lieutenant in 1861, Mahan served as an officer on USS Worcester and James Adger and as an instructor at the Naval Academy. In 1865, he was promoted to lieutenant commander, and then to commander (1872), and captain (1885). As commander of the USS Wachusett he was stationed at Callao, Peru, protecting U.S. interests during the final stages of the War of the Pacific.[7][8]

While in actual command of a ship, his skills were not exemplary; and a number of vessels under his command were involved in collisions with both moving and stationary objects. He preferred old square-rigged vessels rather than smoky, noisy steamships of his own day; and he tried to avoid active sea duty.[9]

[edit]

In 1885, he was appointed as a lecturer in naval history and tactics at the Naval War College. Before entering on his duties, College President Rear Admiral Stephen B. Luce pointed Mahan in the direction of writing his future studies on the influence of sea power. During his first year on the faculty, he remained at his home in New York City researching and writing his lectures. Though he was prepared to become a professor in 1886, Luce was given command of the North Atlantic Squadron, and Mahan became President of the Naval War College by default (June 22, 1886 – January 12, 1889, July 22, 1892 – May 10, 1893).[10] There, in 1888, he met and befriended future president Theodore Roosevelt, then a visiting lecturer.[11]

Mahan’s lectures, based on secondary sources and the military theories of Antoine-Henri Jomini, became his sea-power studies: The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783 (1890); The Influence of Sea Power upon the French Revolution and Empire, 1793–1812 (2 vols., 1892); Sea Power in Relation to the War of 1812 (2 vols., 1905), and The Life of Nelson: The Embodiment of the Sea Power of Great Britain (2 vols., 1897). Mahan stressed the importance of the individual in shaping history and extolled the traditional values of loyalty, courage, and service to the state. Mahan sought to resurrect Horatio Nelson as a national hero in Britain and used his biography as a platform for expressing his views on naval strategy and tactics. Mahan was criticized for so strongly condemning Nelson’s love affair with Lady Emma Hamilton, but it remained the standard biography until the appearance of Carola Oman‘s Nelson, 50 years later.[12]

Mahan struck up a friendship with pioneering British naval historian Sir John Knox Laughton, the pair maintaining the relationship through correspondence and visits when Mahan was in London. Mahan was later described as a “disciple” of Laughton, but the two were at pains to distinguish between each other’s line of work. Laughton saw Mahan as a theorist while Mahan called Laughton “the historian”.[13] Mahan worked closely with William McCarty Little, another critical figure in the early history of the Naval War College. A principal developer of wargaming in the United States Navy, Mahan credited Little for assisting him with preparing maps and charts for his lectures and first book.[citation needed]

Origin and limitation of strategic views[edit]

Mahan’s views were shaped by 17th-century conflicts between the Dutch Republic, the Kingdom of England, the Kingdom of France, and Habsburg Spain, and by the naval conflicts between France and Spain during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. British naval superiority eventually defeated France, consistently preventing invasion and an effective blockade. Mahan emphasized that naval operations were chiefly to be won by decisive battles and blockades.[14] In the 19th century, the United States sought greater control over its seaborne commerce in order to protect its economic interests which relied heavily on exports bound mainly for Europe.

According to Peter Paret‘s Makers of Modern Strategy from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age, Mahan’s emphasis on sea power as the most important cause of Britain’s rise to world power neglected diplomacy and land arms. Furthermore, theories of sea power do not explain the rise of land empires, such as Otto von Bismarck‘s German Empire or the Russian Empire.[15]

Sea power[edit]

Mahan believed that national greatness was inextricably associated with the sea, with its commercial use in peace and its control in war; and he used history as a stock of examples to exemplify his theories, arguing that the education of naval officers should be based on a rigorous study of history. Mahan’s framework derived from Jomini, and emphasized strategic locations (such as choke points, canals, and coaling stations), as well as quantifiable levels of fighting power in a fleet. Mahan also believed that in peacetime, states should increase production and shipping capacities and acquire overseas possessions, though he stressed that the number of coal fueling stations and strategic bases should be limited to avoid draining too many resources from the mother country.[16]

The primary mission of a navy was to secure the command of the sea, which would permit the maintenance of sea communications for one’s own ships while denying their use to the enemy and, if necessary, closely supervise neutral trade. Control of the sea could be achieved not by destruction of commerce but only by destroying or neutralizing the enemy fleet. Such a strategy called for the concentration of naval forces composed of capital ships, not too large but numerous, well-manned with crews thoroughly trained, and operating under the principle that the best defense is an aggressive offense.[17]

Mahan contended that with a command of the sea, even if local and temporary, naval operations in support of land forces could be of decisive importance. He also believed that naval supremacy could be exercised by a transnational consortium acting in defense of a multinational system of free trade. His theories, expounded before the submarine became a serious factor in warfare, delayed the introduction of convoys as a defense against the Imperial German Navy‘s U-boat campaign during World War I. By the 1930s, the U.S. Navy had built long-range submarines to raid Japanese shipping; but in World War II, the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces, still tied to Mahan, designed its submarines as ancillaries to the fleet and failed to attack American supply lines in the Pacific. Mahan’s analysis of the Spanish-American War suggested to him that the great distances in the Pacific required the American battle fleet to be designed with long-range striking power.[18]

Mahan believed first, that good political and naval leadership was no less important than geography when it came to the development of sea power. Second, Mahan’s unit of political analysis insofar as sea power was concerned was a transnational consortium, rather than a single nation state. Third, his economic ideal was free trade rather than autarky. Fourth, his recognition of the influence of geography on strategy was tempered by a strong appreciation of the power of contingency to affect outcomes.[19]

In 1890, Mahan prepared a secret contingency plan for war between the British Empire and the United States. Mahan believed that if the Royal Navy blockaded the East Coast of the United States, the US Navy should be concentrated in one of its ports, preferably New York Harbor with its two widely separated exits, and employ torpedo boats to defend the other harbors. This concentration of the U.S. fleet would force the British to tie down such a large proportion of their navy to watch the New York exits that other American ports would be relatively safe. Detached American cruisers should wage “constant offensive action” against the enemy’s exposed positions; and if the British were to weaken their blockade force off New York to attack another American port, the concentrated U.S. fleet could capture British coaling ports in Nova Scotia, thereby seriously weakening British ability to engage in naval operations off the American coast. This contingency plan was a clear example of Mahan’s application of his principles of naval war, with a clear reliance on Jomini’s principle of controlling strategic points.[20]

Impact[edit]

Timeliness contributed no small part to the widespread acceptance of Mahan’s theories. Although his history was relatively thin, based as it was on secondary sources, his vigorous style, and clear theory won widespread acceptance of navalists and supporters of the New Imperialism in Africa and Asia.

Given the rapid technological changes underway in propulsion (from coal to oil and from reciprocating engines to turbines), ordnance (with better fire directors, and new high explosives), and armor and the emergence of new craft such as destroyers and submarines, Mahan’s emphasis on the capital ship and the command of the sea came at an opportune moment.[17]

Mahan’s name became a household word in the Imperial German Navy after Kaiser Wilhelm II ordered his officers to read Mahan, and Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz (1849–1930) used Mahan’s reputation to finance a powerful High Seas Fleet.[21] Tirpitz, an intense navalist who believed ardently in Mahan’s dictum that whatever power rules the sea also ruled the world, had The Influence of Sea Power Upon History translated into German in 1898 and had 8,000 copies distributed for free as a way of pressuring the Reichstag to vote for the First Navy Bill.[22]

Tirpitz used Mahan not only as a way of winning over German public opinion but also as a guide to strategic thinking.[23] Before 1914, Tirpitz completely rejected commerce raiding as a strategy and instead embraced Mahan’s ideal of a decisive battle of annihilation between two fleets as the way to win command of the seas.[22] Tirpitz always planned for the German High Seas Fleet to win the Entscheidungsschlacht (decisive battle) against the British Grand Fleet somewhere in “the waters between Helgoland and the Thames“, a strategy he based on his reading of The Influence of Sea Power Upon History.[22]

However, the naval warfare of World War I proved completely different than German planners, influenced by Mahan, had anticipated because the Royal Navy avoided open battle and focused on blockading Germany. As a result, after the Battles of Heligoland Bight and Dogger Bank, Admiral Hugo von Pohl kept most of Germany’s surface fleet at its North Sea bases. In 1916, his successor, Reinhard Scheer, tried to lure the Grand Fleet into a Mahanian decisive battle at the Battle of Jutland, but the engagement ended in a strategic defeat.[24] Finally as the German army neared defeat in the Hundred Days Offensive, the German government tried to mobilize the fleet for a decisive engagement with the Royal Navy. The sailors then rebelled in the Kiel mutiny, instigating the German Revolution of 1918–1919, which toppled the Hohenzollern monarchy and forced the new government to sue for peace.[25]

Mahan and British First Sea Lord John Fisher (1841–1920) both addressed the problem of how to dominate home waters and distant seas with naval forces unable to do both. Mahan argued for a universal principle of concentration of powerful ships in home waters with minimized strength in distant seas. Fisher instead decided to use submarines to defend home waters and mobile battlecruisers to protect British interests.[26]

Though in 1914, French naval doctrine was dominated by Mahan’s theory of sea power, the course of World War I changed ideas about the place of the navy. The refusal of the German fleet to engage in a decisive battle, the Dardanelles expedition of 1915, the development of submarine warfare, and the organization of convoys all showed the French Navy‘s new role in combined operations with the French Army. The Navy’s part in securing victory was not fully understood by French public opinion in 1918, but a synthesis of old and new ideas arose from the lessons of the war, especially by Admiral Raoul Castex (1878–1968), who synthesized in his five-volume Théories Stratégiques the classical and materialist schools of naval theory. He reversed Mahan’s theory that command of the sea precedes maritime communications and foresaw the enlarged roles of aircraft and submarines in naval warfare.[27]

The Influence of Seapower Upon History, 1660–1783 was translated into Japanese[28] and was used as a textbook in the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). That usage strongly affected the IJN’s plan to end Russian naval expansion in the Far East, which culminated in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05.[29] It has been argued that the IJN’s pursuit of the “decisive battle” (Kantai Kessen) contributed to Imperial Japan‘s defeat in World War II,[30][31] because the development of the submarine and the aircraft carrier, combined with advances in technology, largely rendered obsolete the doctrine of the decisive battle between fleets.[32] Nevertheless, the IJN did not adhere strictly to Mahanian doctrine because its forces were often tactically divided, particularly during the attack on Pearl Harbor and the Battle of Midway.

Mahan believed that if the United States were to build an Isthmian canal, it would become a Pacific power, and therefore it should take possession of Hawaii to protect the West Coast.[33] Nevertheless, his support for American imperialism was more ambivalent than is often stated, and he remained lukewarm about American annexation of the Philippines.[34] Mahan was a major influence on the Roosevelt family. In addition to Theodore, he corresponded with Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt until his death in 1914. During World War II, Roosevelt would ignore the late Mahan’s prior advice to him that the Commonwealth of the Philippines could not be defended against an Imperial Japanese invasion, leading to a futile defense of the islands against the Japanese Philippines campaign.[35]

Between 1889 and 1892, Mahan was engaged in special service for the Bureau of Navigation, and in 1893 he was appointed to command the powerful new protected cruiser Chicago on a visit to Europe, where he was feted. He returned to lecture at the War College and then, in 1896, he retired from active service, returning briefly to duty in 1898 to consult on naval strategy during the Spanish–American War.

Mahan continued to write, and he received honorary degrees from Oxford, Cambridge, Harvard, Yale, Columbia, Dartmouth, and McGill. In 1902, Mahan popularized the term “Middle East,” which he used in the article “The Persian Gulf and International Relations,” published in September in the National Review.[36]

As a delegate to the 1899 Hague Convention, Mahan argued against prohibiting the use of asphyxiating gases in warfare on the ground that such weapons would inflict such terrible casualties that belligerents would be forced to end wars more quickly, thus providing a net advantage for world peace.[37]

In 1902, Mahan was elected president of the American Historical Association, and his address, “Subordination in Historical Treatment”, is his most explicit explanation of his philosophy of history.[38]

In 1906, Mahan became rear admiral by an Act of Congress that promoted all retired captains who had served in the American Civil War. At the outbreak of World War I, he published statements favorable to the cause of the Allies, but in an attempt to enforce American neutrality, President Woodrow Wilson ordered that all active and retired officers refrain from publicly commenting on the war.[39]

Mahan was reared as an Episcopalian and became a devout churchman with High Church sympathies. For instance, late in life he strongly opposed revision of the Book of Common Prayer.[40] Nevertheless, Mahan also appears to have undergone a conversion experience about 1871, when he realized that he could experience God’s favor, not through his own merits, but only through “trust in the completed work of Christ on the cross.”[41] Geissler called one of his religious addresses almost “evangelical, albeit of the dignified stiff-upper-lip variety.”[42] And Mahan never mentioned a conversion experience in his autobiography.

In later life, Mahan often spoke to Episcopal parishes. In 1899, at Holy Trinity Church in Brooklyn, Mahan emphasized his own religious experience and declared that one needed a personal relationship with God given through the work of the Holy Spirit.[43] In 1909, Mahan published The Harvest Within: Thoughts on the Life of the Christian, which was “part personal testimony, part biblical analysis, part expository sermon.”[44]

Mahan died in Washington, D.C., of heart failure on December 1, 1914, a few months after the outbreak of World War I.

- Four ships have been named USS Mahan, including the lead vessel of a class of destroyers.

- The United States Naval Academy‘s Mahan Hall was named in his honor,[45] as was Mahan Hall at the Naval War College. (Mahan Hall at the United States Military Academy was named for his father, Dennis Hart Mahan.)

- A. T. Mahan Elementary School and A. T. Mahan High School at Keflavik Naval Air Station, Iceland, were named in his honor.

- A former mission school in Yangzhou, China, was named for Mahan.[46]

- A U.S. Naval Sea Cadet Corps unit in Albany, New York, is named for both Mahan and his father.[47]

- Mahan Road is an entrance to the former Naval Ordnance Laboratory in White Oak, Silver Spring, Maryland]. The facility is now the headquarters of the Food and Drug Administration.

Alfred Thayer Mahan married Ellen Lyle Evans in June 1872; they had two daughters and one son.